- Everything

- Excluding groups

- MOOC Participants

Active Learning and Citizen Science

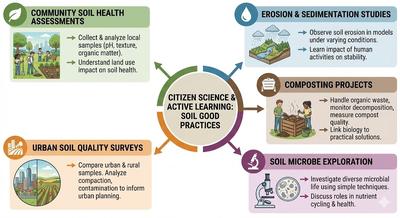

Now, let’s channel inclusion and safety into action. Section 4 focuses on active learning and citizen science, where students move from passive observers to soil advocates. Explore how to integrate low-cost, high-impact projects, like local soil testing or digital storytelling about land stewardship, that align with curricula while fostering civic agency. These methods honour secondary students’ growing autonomy, showing them their voices matter in shaping a sustainable future. Active learning is an educational approach that emphasizes students' direct engagement with the material, fostering deeper understanding and retention. Integrating active learning into your teaching practice can enhance students' critical thinking, problem-solving, and collaborative skills. This method involves moving beyond traditional lectures to incorporate activities that require students to actively process and apply information. A key aspect of active learning is the application of theoretical concepts to real-world contexts. By bridging the gap between theory and practice, students gain valuable insights into how their classroom knowledge applies to societal challenges. This approach not only enriches learning but also prepares students to become informed, proactive citizens. Citizen science is a compelling extension of active learning, empowering students to contribute to genuine scientific research. By participating in citizen science projects, students engage meaningfully with scientific methodologies and contribute to data collection and analysis. These projects foster a sense of ownership and responsibility, encouraging students to apply their learning to benefit society. To integrate authentic citizen science and civic engagement into your curriculum, the HUMUS Project's "Soil Stewards" initiative offers an interesting framework. By providing structured protocols, training, and tools, it enables educators to guide students in collecting valuable scientific data on local soil health . By connecting local soil data to broader EU sustainability goals, the project naturally fosters civic awareness. Students see how their scientific work informs larger conversations about land use, food security, and climate policy, demonstrating the power of collective action and empowering them as informed, engaged citizens capable of contributing to solutions for planetary challenges. Here are some good practices that exemplify active learning and the application of theoretical concepts in real contexts through citizen science: Community soil health assessments: Organize students to collect and analyse soil samples from various local habitats, such as gardens, parks, and agricultural fields. By testing for soil pH, texture, and organic matter content, students can apply soil science concepts to understand the influence of different land use practices on soil health. This hands-on activity encourages critical thinking about sustainable land management. Erosion and sedimentation studies: Set up simple experiments where students create models to observe soil erosion under different conditions, such as varying vegetation cover or rainfall intensity. By connecting theoretical principles of erosion to visible results, students learn about the impact of human activities on soil stability and the practical measures to prevent it. Composting projects: Implement a school composting program where students handle organic waste, monitor decomposition stages, and measure the quality of the resulting compost. This project links classroom learning about biological processes and nutrient cycling with practical environmental solutions that enhance soil fertility and reduce waste. Soil microbe exploration: Involve students in investigating the diverse microbial life present in soil samples. Using simple microbiology techniques, students can cultivate and identify microorganisms, discussing their roles in nutrient cycling and plant health. This exploration deepens understanding of the unseen biodiversity within soil and its ecological importance. Urban soil quality surveys: Guide students to examine the impact of urbanization on soil quality by comparing samples from urban and rural areas. Analysing differences in soil compaction, contamination, and organic content reveals crucial insights into urban planning and sustainable development. How would you use active learning in your class when teaching about soil? Write a short reflection! Reflection ‘Tell the story of that soil’: write a creative piece or a research story about the ‘life’ of that soil - where it comes from, what organisms live in it, what crops grow there and how it might change in the future. This approach can encourage empathy for natural systems, creativity and the integration of scientific and narrative thinking. Share in the Forum Conclusion Soil literacy is more than a subject, it’s a catalyst for connection. This module has equipped you with strategies to transform your classroom into a space where diverse learners see themselves in the story of soil, where trauma-informed practices foster safety, and where citizen science turns abstract concepts into tangible action. By prioritizing inclusion and student agency, you’re not just teaching about soil health; you’re modeling how to engage with complex global issues thoughtfully and equitably. For secondary teachers, this work is critical: adolescents are forming their identities as citizens, scientists, and stewards. Your lessons can help them navigate climate anxiety with purpose, grounding fear in actionable hope. The tools you’ve explored in this module, universal design frameworks, trauma-conscious scaffolding, and citizen science projects, are not extra tasks. They’re ways to simplify your practice by meeting students where they are. A soil pH lab becomes a dialogue about environmental justice. A composting project doubles as a lesson in collaboration. As you move forward, remember that small, intentional shifts, like offering choice in assessments or partnering with a local NGO, can ripple outward, shaping not just skilled learners, but empathetic advocates for the Earth. You hold the seeds; let this module be your toolkit for helping them grow.

Trauma-Conscious Education

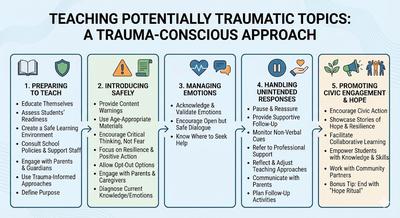

Even the most thoughtfully designed lessons can fail if students carry unspoken burdens. Section 3 addresses trauma-conscious education, acknowledging that climate anxiety, displacement, or agricultural inequities may shape how students engage with soil topics and life. Discover subtle strategies to create psychological safety, like grounding discussions in solutions rather than doom, or offering choice in how students participate. This isn’t about therapy, it’s about teaching with awareness. Before diving into practical terms, it can be valuable to build a foundational understanding of trauma's impact on learning and school environments. A starting point is the US National Education Association (NEA), which offers comprehensive reflections and resources specifically designed for educators on creating Trauma-Informed Schools (TIS). The NEA provides practical guidance, policy recommendations, classroom strategies, and professional development tools focused on shifting school culture to recognize signs of trauma, respond supportively, prevent re-traumatization, and foster resilience among all students. On a broader theoretical and societal level, exploring the extensive body of work by Dr. Gabor Maté offers profound insights into the origins and pervasive effects of trauma, particularly childhood trauma. Dr. Maté, a renowned physician and author (known for works like Scattered Minds and The Myth of Normal), delves deeply into the mind-body connection, addiction, stress, and how early adverse experiences shape development and behavior. His vast library of accessible online material – including lectures, interviews, podcasts, and articles – provides a crucial lens for understanding the why behind the behaviors and challenges educators encounter, emphasizing compassion and the healing power of secure relationships. Introducing Potentially Traumatic Topics Teaching topics such as soil threats, climate change, the Holocaust, racial injustices, war, or genocide is crucial in education. These subjects help students develop critical thinking, empathy, resilience and civic responsibility. However, they can also cause emotional distress or trigger trauma in students. Teaching such topics requires sensitivity, preparation, and support. By adopting trauma-informed approaches, fostering resilience, and providing students with the tools to take action, professional educators can ensure that these lessons contribute to both personal growth and a healthier society. The following list of to-dos will help you make sure that you have covered many aspects of trauma-conscious education. If you are interested, you can check out the full guide here. 1. Preparing to Teach Sensitive Topics Before addressing sensitive or potentially traumatic subjects, teachers should: Educate Themselves: Understand the historical, social, and psychological dimensions of the topic. Assess Students’ Readiness: Consider students’ age, maturity, and personal experiences. Create a Safe Learning Environment: Establish classroom norms of respect, openness, and support. Consult School Policies & Support Staff: Collaborate with counsellors, school psychologists, and administrators to ensure adequate support structures are in place. Engage with Parents & Guardians: Inform parents ahead of time about the topics being covered. Provide context, resources, an open channel for discussion, and seek their approval and support for teaching about the topic. Use Trauma-Informed Approaches: Recognize signs of distress and adopt strategies that prioritize student well-being. Have a clear picture of the purpose of addressing the topics: what, how and why. 2. Introducing Difficult Topics Safely To prevent harm while addressing these issues: Provide Content Warnings: Inform students in advance when discussing distressing topics. Use Age-Appropriate Materials: Select resources suited to the cognitive and emotional development of students. Be aware that visual content can have more traumatising effect than texts. Encourage Critical Thinking, Not Fear: Frame discussions in ways that empower students rather than overwhelm them. Focus on Resilience & Positive Action: Highlight examples of courage, resistance, and solutions to counter feelings of helplessness. Allow Opt-Out Options: Give students alternatives if they feel uncomfortable engaging in discussions. Engage with Parents & Caregivers: Have full engagement of parents in the learning and educating process and provide them with take-home discussion guides or similar resources so that families can reinforce learning in a supportive environment. Diagnose on what level the students’ knowledge and emotions on the matter are at the moment, so you understand the current situation. 3. Managing Emotional Responses & Trauma Prevention Some students may react strongly to difficult topics. Teachers should: Acknowledge & Validate Emotions: Recognize students’ feelings without dismissing or amplifying their distress. Encourage Open but Safe Dialogue: Guide discussions constructively while preventing re-traumatization. Know Where to Seek Help: Teachers should be familiar with local and national mental health resources, school counselling services, and organizations specializing in trauma-informed education. 4. Handling Unintended Trauma Responses If a student experiences distress during or after discussions: Pause & Reassure: Offer immediate reassurance and, if needed, a break from the discussion. Provide Supportive Follow-Up: Check in with the student privately to assess their well-being. Monitor Non-Verbal Cues: Be aware of students who may withdraw or show signs of distress. Drastic changes of eating habits and/or appearance must be investigated. Refer to Professional Support: If distress persists, refer the student to school counsellors, psychologists, or external mental health professionals. Reflect & Adjust Teaching Approaches: Consider modifying lesson plans or classroom discussions based on student feedback. Communicate with Parents: If a student experiences significant distress, it may be beneficial to reach out to their parents or guardians to ensure they receive additional support at home. If possible, plan follow-up activities after the session that support emotional regulation and a return to calm, such as physical movement, relaxation exercises, or embodied practices for emotional release. 5. Promoting Civic Engagement & Hope Difficult topics should not leave students feeling powerless. Instead: Encourage Civic Action: Provide opportunities for students to engage in advocacy, volunteer work, or community projects Showcase Stories of Hope & Resilience: Highlight individuals and movements that have made a positive impact. Facilitate Collaborative Learning: Encourage students to work together in discussions and projects that promote constructive change. Empower Students with Knowledge & Skills: Teach media literacy, conflict resolution, and democratic participation and resilience. Work with Community Partners: Involve local organizations, guest speakers, and activists (when appropriate) to provide diverse perspectives and real-world connections. Bonus tip: After heavy lessons, end with a "hope ritual" (e.g., students share one action they can take to make a difference). Key Takeaways for Educators: Prepare thoroughly and create a safe environment. Use content warnings and age-appropriate materials. Encourage critical thinking without inducing fear. Monitor and support students emotionally. Engage parents and guardians as partners in the learning process. Know where to seek professional support when needed. Promote action, resilience, and civic engagement.

- Copy link

In the quiz, the 4th question has a correct answer different from the corresponding question in the primary teachers' MOOC. All the correct answers are the longer ones: revise this aspect.

- Copy link

See the comments in the Primary Teachers' MOOC.

Universal Design and Student-Centred Teaching Methods

Creating inclusive soil literacy starts with intention, and it demands energy. Building on the considerations from Section 1, Section 2 introduces universal design frameworks to structure lessons that are accessible by default. Learn to adapt soil experiments, discussions, and assessments for neurodiverse learners, students with disabilities, or those facing language barriers. These approaches don’t just accommodate differences—they enrich everyone’s learning. Universal Design for Learning is a framework aimed at optimizing teaching and learning for everyone, leveraging scientific insights into how humans learn. The goal of UDL is learner agency that is purposeful and reflective, resourceful and authentic, strategic and action-oriented. Learn more here. Student-centred teaching methods engage children as active participants in the classroom, ensuring their involvement in both planning and evaluation of innovative school programs. Check out the following methods for Student-centred teaching: Project-based learning involves students working on extended projects that tackle real-world problems. This method develops deep content knowledge along with critical skills like thinking, collaboration, and communication. For example, students might create a soil conservation plan for a community garden, allowing them to apply their knowledge to practical soil literacy challenges. Problem-based learning (PBL) has students identify learning objectives by exploring real-world scenarios. This approach inverts traditional learning by empowering students to explore topics they deem necessary. An example of this method in action is investigating causes of soil erosion and developing solutions that can be implemented in local communities. PBL typically follows the Maastricht seven-jump process: understanding the problem, identifying questions, brainstorming current knowledge and potential solutions, structuring the results, setting learning objectives for missing knowledge, conducting independent study, and discussing findings with the group. Inquiry-based learning offers students the opportunity to pinpoint problems and chart out their own exploratory routes, making it particularly suitable for digitally supported learning. An instance of this approach might involve students exploring different soil types in local parks and documenting their findings using digital tools, thereby enhancing soil literacy through independent research and discovery. Experiential learning focuses not just on learning outcomes but also on the experiences and emotions of students during their learning journey. This method is particularly valuable for environmental topics that might otherwise be distressing. For example, students conduct soil health experiments that allow them to understand environmental impacts, linking emotional engagement with educational content. Playful learning introduces serious play to the educational process, fostering an ideal learning state that balances challenge and engagement. By emphasizing joy, largely informed by Csíkszentmihályi’s flow theory, it adds a joyful element to serious learning. Students might role-play managing a farm with a focus on soil health, experiencing joy through achievement and surprise. Gamification adapts game elements to enhance learning activities, boosting interest and motivation without necessarily incorporating actual games. In a classroom setting, this could mean students earn points for identifying soil nutrients accurately, while not being penalized for incorrect answers, thus maintaining motivation and focus on learning goals. Game-based learning incorporates game-like activities intrinsically into the learning process. Educational games are purposefully designed to teach specific subjects. For instance, students might engage with a farming simulation game where they manage soil fertility, gaining hands-on experience in agricultural practices and soil management strategies. These methods should be adaptable to meet individual students' needs. Teachers must genuinely believe in and be comfortable with the methods they apply. Offering students a choice in their teachers and learning methods, supported by incentives for schools, can facilitate tailored and effective educational experiences.

- Copy link

In the quiz, once again, the correct answers are the longer answers, which may influence the responses. This is an issue that should be revised in all the MOOC quizes. In this quiz, once again, there is a lack of feedback explaining the answers.

- Copy link

It is not clear the difference between gamification and Playful learning. More explicit examples should be provided to clarify it. Another aspect is that considering the MOOC for Primary teachers it is not clear what are the specificities of each teaching level.

ACTIONS FOR INCLUSIVE SOIL LITERACY EDUCATION

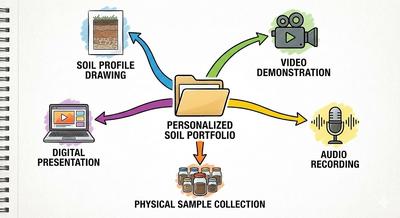

1. Incorporate multi-sensory learning approaches Set up "Soil sensing stations" around the classroom where students rotate through different sensory experiences: Touch station: Soil texture assessment using the "feel method" with different soil types in labelled containers Smell station: Identifying earthy aromas of healthy soils versus compacted ones Visual station: Microscopes or magnifying glasses to observe soil components Sound station: Audio recordings of water percolating through different soil types 2. Connect soil education to local cultural context Relate soil science to local agricultural traditions, food systems, and cultural practices specific to your European region. Students can interview family members or research traditional agricultural practices from their cultural backgrounds, creating a classroom "Soil heritage map" showing different approaches to soil management across cultures. This helps make learning relevant for students from different cultural backgrounds. 3. Implement Universal Design for Learning (UDL) Provide flexible learning materials and multiple ways for students to engage with and demonstrate their understanding of soil concepts. Students can analyse soil health using multiple formats: - Digital soil testing apps with voice commands - Colour-changing test strips with large-print result guides - Physical manipulation tests with guided worksheets - Group collaboration options for those who benefit from peer support 4. Develop inclusive assessment methods Offer diverse ways for students to demonstrate soil knowledge. Students can create personalized soil literacy portfolios choosing from options like: Soil profile drawings with annotations Video demonstrations of soil tests Audio recordings explaining soil functions Physical soil sample collections with descriptions Digital presentations on soil organisms This respects different communication styles and abilities.

- Copy link

There is a mistake in a word in the 4th question of the quiz.

- Copy link

The Portuguese flag should be included in the second picture to not descriminate Portuguese teachers. Overal, it is very theoretical with few examples of how to do it in practice.

The unique video from this module is from another project's MOOC. Why this option?