Course Overview - Introduction

In Module 1, we’ll explore why soil is so important - and why it deserves a central place in our and everyone’s learning. We will also provide key background knowledge about soil to spark curiosity and wonder and increase awareness in classrooms across Europe.

Soil is one of the most vital and fascinating parts of our planet. It connects everything: the solid earth (lithosphere), water (hydrosphere), air (atmosphere), and all living things (biosphere). We rely on soil every day - we walk on it, grow food in it, build homes on it, and enjoy nature through it. Yet many people overlook just how essential it is. Soil is quite literally the foundation of life on land.

Humans have always had a deep connection with soil, and learning about it helps us understand our environment, our history, and our future. In this module, we’ll look at soil as a living, dynamic ecosystem - a place full of life, culture, and change. We'll also see how soil can inspire curiosity, creativity, and action, helping students feel more deeply connected to the natural world and willing to become active in its protection and restoration, literally from the ground up.

This module unearths why soil literacy belongs at the heart of education. We’ll explore soil as a living ecosystem, a cultural heritage, and a catalyst for student agency—equipping you to transform "dirt" into dynamic learning that roots students in their world.

So, what makes soil so fascinating and essential? Let’s dig deeper and find out.

|

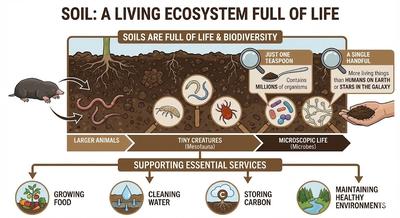

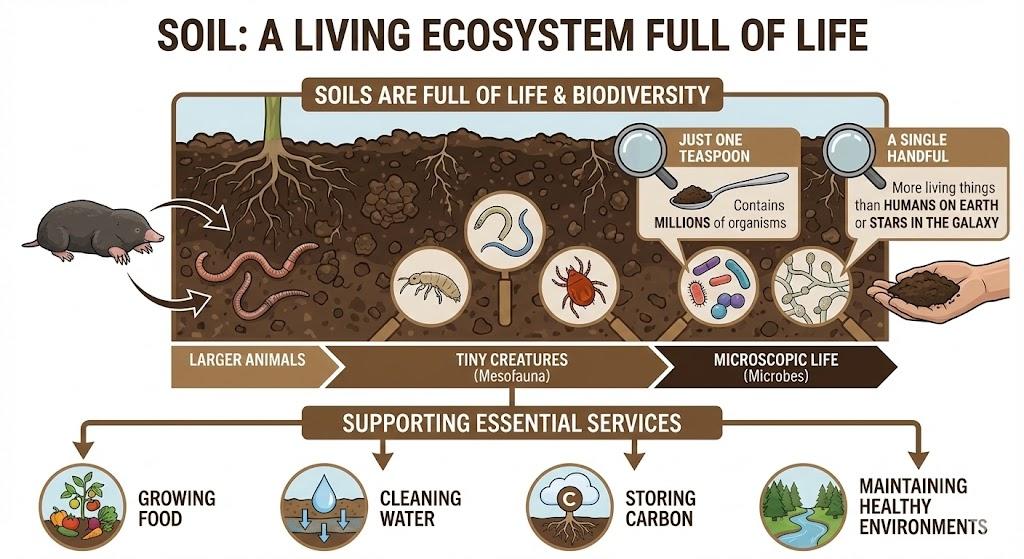

1. Soils are full of life. Soils are living ecosystems full of life. In fact, they host more biodiversity than almost any other place on Earth. Only in recent years have scientists - and society as a whole - begun to truly appreciate how important soil life is. The incredible variety of organisms in soil helps support many essential services, like growing food, cleaning water, storing carbon, and maintaining healthy environments. A recent estimate suggests that nearly 60% of all species on Earth live in the soil. These range from larger animals like moles and earthworms, to tiny creatures like springtails, nematodes, and mites, and all the way down to microscopic bacteria and fungi. Just one teaspoon of soil can hold millions of organisms, most of them invisible to the naked eye. And in a single handful of soil, there are more living things than there are humans on Earth - or even stars in the galaxy. |

|

|

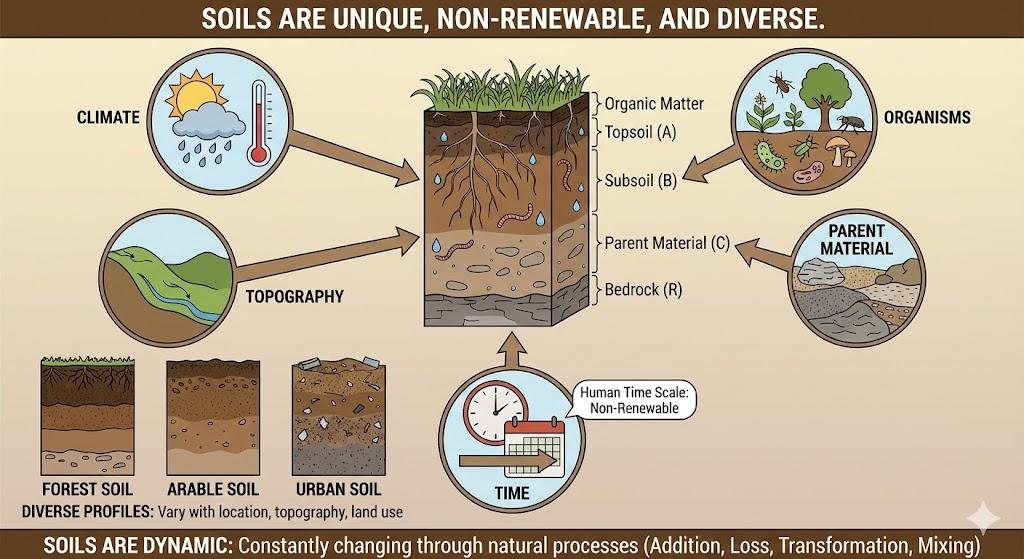

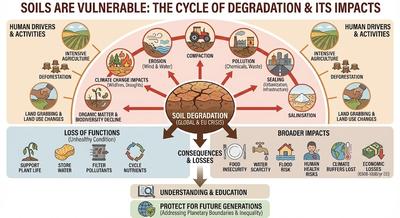

2. Soils are unique, non-renewable, and diverse. Soils are unique, incredibly diverse, and non-renewable within a human time scale. If you dig into the ground in different parts of the world, you’ll see profiles with layers of different colors and characteristics. Also on a smaller scale, soils vary a lot when considering topography or land use – Check out how an urban soil looks different form a forest, arable or wetland soil! The Russian geologist Vasily Dokuchaev (1846-1903) is considered the father of soil science. His big insight is that soil is continually evolving, and is specific to each site. Soil formation is influenced by five main factors: climate, topography (land shape), organisms (plants, animals, and microbes), the type of parent material (rock or sediment), and time. These factors work together to create soils that are complex, living ecosystems, made up of minerals, organic matter, water, air, and a wide range of life - including bacteria, fungi, insects, and plant roots. Soils are not static. They are constantly changing through natural processes like the addition of new material (like fallen leaves), the loss of nutrients (e.g. taken up by plants or lost through leaching into deeper parts of the soil or into groundwater), chemical transformations, and physical mixing. Because of these processes, soils vary greatly from place to place and even change over time. |

|

|

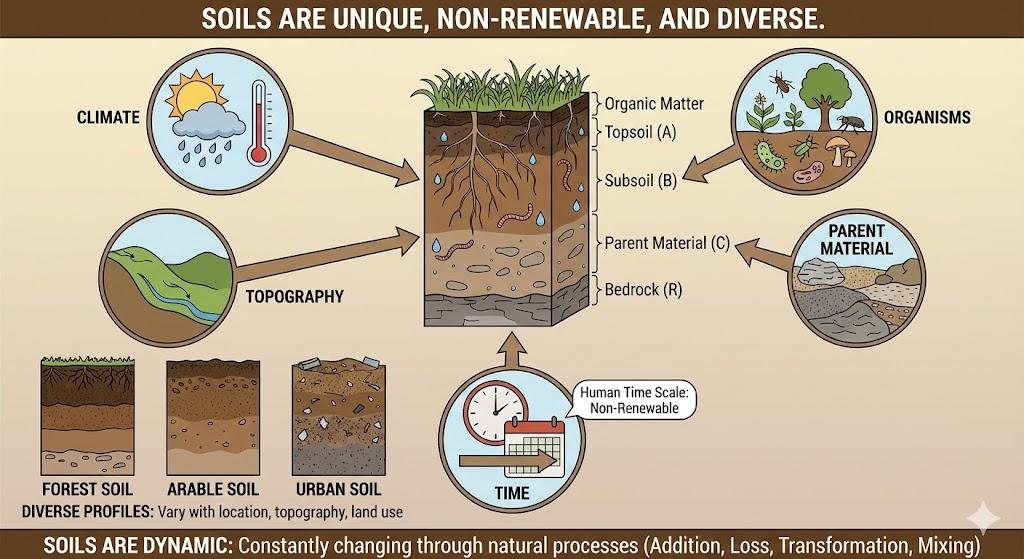

3. Soilsare essential to our life and wellbeing, and to the functioning of the Earth system.

Soil is also full of life. It’s home to countless organisms - from tiny insects and earthworms to small mammals. These creatures keep the soil healthy by breaking down organic matter and recycling nutrients. Some, like ants and earthworms, are known as "ecosystem engineers" because they shape the soil in ways that benefit other living things. Even the tiniest life forms in soil - microbes - play a big role. While some can cause illness, many are essential for our health. They help protect us from allergies and even provide us with medicines like antibiotics. Microbes also influence the air we breathe by controlling the exchange of gases like carbon and nitrogen between the soil and the atmosphere - which plays a major part in climate regulation. Soil also tells stories. It holds clues about the past, like a treasure chest or a time machine. Over time, soil covers and preserves remains of past human life - ancient tools, buildings, bones, and pottery. When archaeologists uncover these items, we learn more about how people lived, what they valued, and how our societies have changed. Despite what we already know there's still so much left to discover, especially about the hidden world of microscopic life in the soil. Unfortunately, most people don’t give soil much thought, even though our lives depend on it every day. That’s where we come in. Together, we can help spread the word about the wonders of soil - and why it’s worth and essential protecting, studying, and celebrating. |

|

|

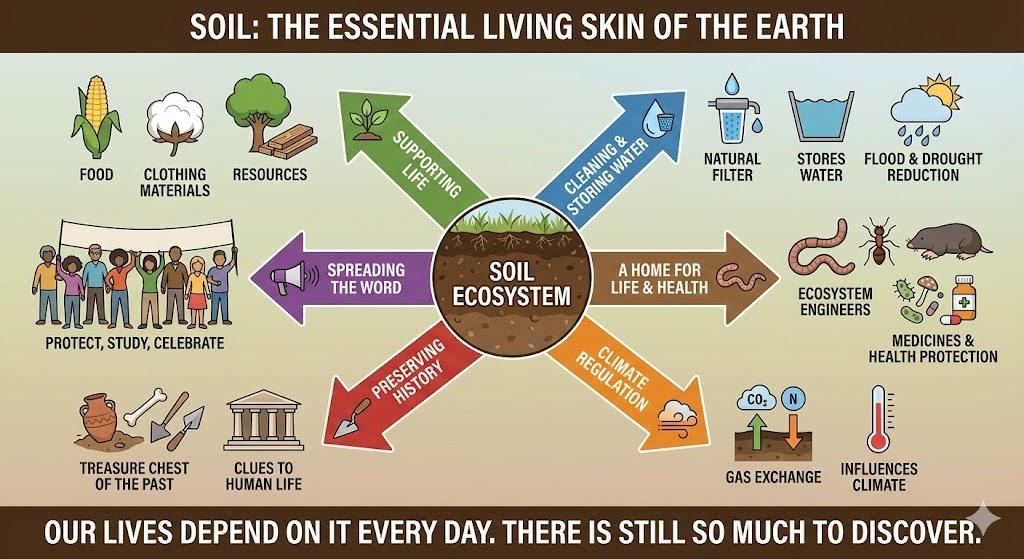

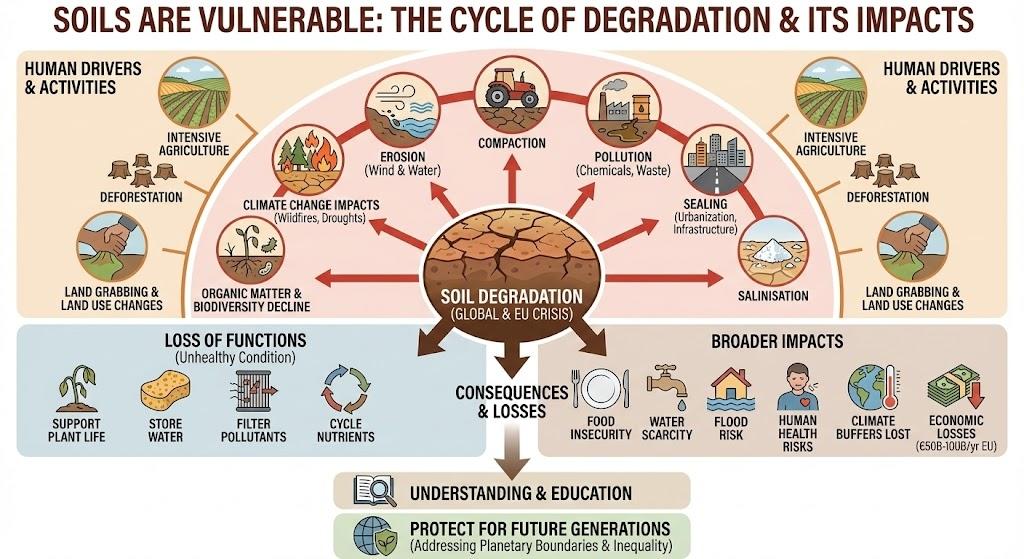

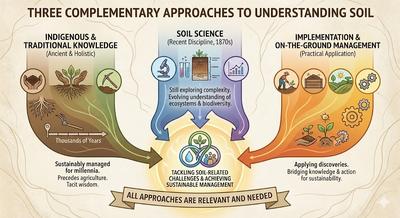

4. Soilsare vulnerable

Currently, more than half of the world’s soils are considered degraded and more than 60% of soils in Europe are in an unhealthy condition. This means they’re losing their ability to function properly - to support plant life, store water, filter pollutants, and cycle nutrients and therefore essential for food security, water availability and quality, contributing to flood control, functioning of ecosystem, human health, buffering of climate change impacts and much more, also causing direct and indirect economic costs or losses, which are estimated between 50 billion to 100 billion Euros a year in the EU alone. Furthermore, agriculture and with-it intensive soil use and often degradation is the major factor in exceeding the planetary boundaries, where seven of nine boundaries have been breached. Soils and their human use, misuse and abuse also reflect not only our extractive and utilitarian often profit driven relation to this essential resource (like with all other ‘natural resources’), but also show up in social relations, inequality and inequity, through who has or has not access and use rights and availability to soil and related resources and uses (e.g. land rights, land grabbing, etc.) Understanding how land use affects soil is essential. By learning and teaching about soil, we can help protect this vital resource and make sure it continues to support life - now and for future generations. |

|

|

5. Soils can be healed

We can care for soil in three key ways:

|

|

|

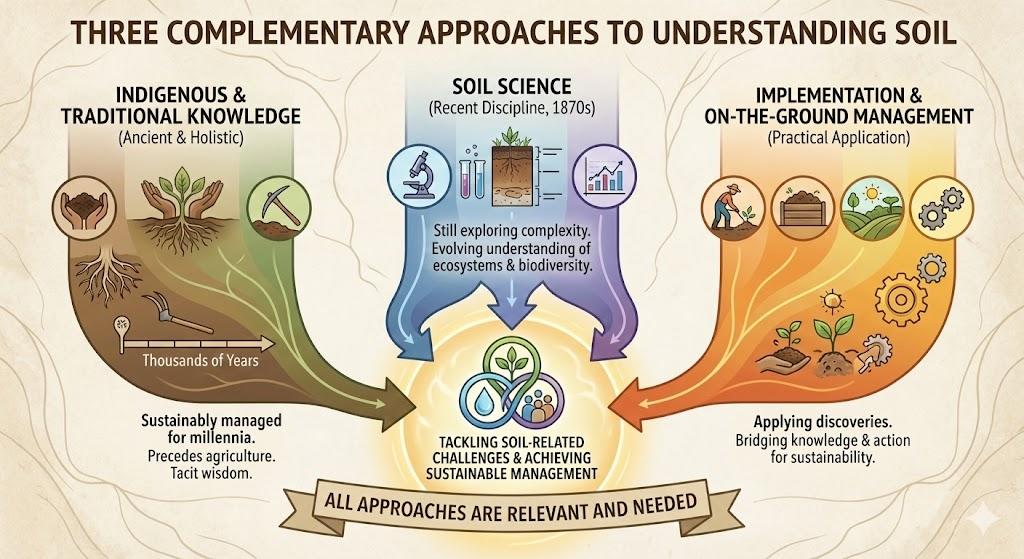

6. Three Complementary Approaches to Understanding Soil Soils can be approached and understood in different ways. and all of them are relevant and needed to tackle soil-related challenges. Soils have often been sustainably managed by indigenous peoples and communities using traditional/tacit knowledge for thousands of years and still are in many parts of the world. This knowledge of soils precedes and goes beyond agriculture. Soil science is a recent discipline (1870s) and the complexity of soils is still not fully scientifically understood. Recent discoveries on soil ecosystems and soil biodiversity still needs to be explored further and more so implemented on the ground to achieve sustainable management of soils. This diversity of knowledge isn’t just academic, it’s practical. For teachers, these three pathways (scientific, agricultural, Indigenous) offer lenses to make soil literacy resonate across cultures and subjects. For school leaders, they provide frameworks to design inclusive, community-anchored programs that honor local wisdom while meeting curricular goals. Beyond the field of soil scientists, different groups have different understandings of what soils are. The ways in which soils are known, represented, and understood are diverse. In different regions, farmers, foresters, government officials, soil researchers, or environmental NGOs know soil in different ways and attach different meanings to it [5]. There is also the historic context of how soil science has emerged and developed as a topic seeking relevance within the scientific community and governance spheres over the past one hundred years, which adds another level of complexity to the discussion. Accounts of the history of soil science usually locate the origins of the discipline in the late 1800 with Vasiliy Dokuchaev [6], then the first international soil science congresses and conferences in 1909, 1924, and 1927 [7]. Based on Dokuchaev’s work, Hans Jenny developed, in the 1940s, a conceptual model of soil formation factors. In the early 1900s, soil-related concepts started developing and being published, such as soil fertility, soil productivity, and soil conservation. Before the 1970s, soil knowledge was mainly related to agricultural practices, and as technologies started developing (e.g., mechanisation, chemicals, and modified plant crops, namely the “first green revolution” [8]), there was a shift in this concept. |

|

1. Scientific soil knowledge.

Soil science is a recent discipline (1870s) and the complexity of soils is still being understood. Recent discoveries on soil ecosystems and soil biodiversity still needs to be implemented to achieve sustainable management of soils. Can be considered to start from Dokuchaev in the 1870s. Historically linked to agricultural expansion in the Eurasian steppe and Northern American prairie.

2. Traditional soil knowledge linked to agricultural management.

Practitioners' knowledge, often in tacit form, and used for day to day management of agroecosystems, especially relevant in the case of smallholders, family farms and indigenous communities.

3. Soil knowledge before and beyond agriculture.

Soils have been sustainably managed by indigenous people and communities using traditional/tacit knowledge for thousands of years and still are in many parts of the world. This soil knowledge is often linked to holistic landscape management and to specific activities like foraging from tubers and roots, hunting underground prey, building dwellings, digging holes to cook or preserve food, as dwellings, or as burial; extracting pigments and clay for artistic, ritual, cosmetic and medicinal purposes, selective burning or backburning on a larger landscape scale to replenish soils with nutrients and/or to selectively manage vegetation or landscape (e.g. for hunting of large animals) and reduce fuel load, nutrient management (e.g. terra preta in the Amazon), etc

It is especially important to acknowledge that soil knowledge precedes and goes beyond agriculture, as most literature links soil knowledge with agriculture and the neolithic revolutions. Brevik and Hartmink (2010), when providing a historical perspective on soil knowledge, fall into an apparent contradiction when stating that “soil knowledge dates to the earliest known practice of agriculture about 11,000 BP.” and then admitting that “humans have always had an intimate relation with the soil”

These knowledge systems aren’t competing, they’re complementary threads in the same tapestry. When we braid them together in our schools, we empower students to see soil not as "dirt," but as a living library of ancestral innovation, scientific discovery, and ecological kinship.

What is soil?

“A natural body consisting of layers (soil horizons) that are composed of weathered mineral materials, organic material, air and water “

All definitions | FAO SOILS PORTAL | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

What is soil health?

The Intergovernmental Technical Panel on Soils (ITPS) defines soil health as “the ability of the soil to sustain the productivity, diversity, and environmental services of terrestrial ecosystems”.

What is soil literacy?

Johnson et al. defines soil literacy as a combination of attitudes, behaviours, and competencies required to make sound decisions that prevent soil degradation, promote soil health, and ultimately contribute to the maintenance and enhancement of the natural environment.

“The Soil Mission Implementation plan understands soil literacy as both a popular awareness about the importance of soil and specialised and practice-oriented knowledge related to achieving soil health [3]. A more detailed definition of what soil literacy entails has been provided by Johnson et al., 2020 [4]: a combination of attitudes, behaviours, and competencies required to make sound decisions that promote soil health and ultimately contribute to the maintenance and enhancement of the natural environment.”

Land 2025, 14(7), 1372; https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071372

Conclusion - from the soil to the whole society:

The case for soil literacy rests on recognizing that soil knowledge is not only older than agricultural practices, but also more fundamentally essential to human life and wellbeing.

Acknowledging the different types of soil related knowledge, practices and wisdomcan also help decolonise soil science and make it more inclusive, fostering dialogue between scientists and practitioners. A broader perspective on soil knowledge and its practices can also connect soil science with social sciences , humanities, history and artistic disciplines and become relevant and important in our everyday lives. Soils touch and shape the lives of all of us, hence it's about time to know, understand, relate to, interact and co-create a mutually beneficial relationship with soils and hence with life itself as part of designing flourishing and regenerative futures for all of life. So what are you waiting for – get your hands into the soil!

Please see comments on Module 1 in the attached file

Missing a space on point 3. "Soils are" and point 4. "Soils are"

On the Soils are vulnerable image, was it intentional to repeat the same human drivers and activities on both sides?

On point 5, Soils can be healed. An important action is to protect trees and bushes already established (usually not understood under deforestation because deforestation is usually seen as large scale actions).